Russia is no longer a post-imperial state. Today it seems to resemble a conserved trans-state, which is neither democratic and modernised nor fully authoritarian and backward. What Moscow considers indisputable from its point of view is the special status it should enjoy globally.

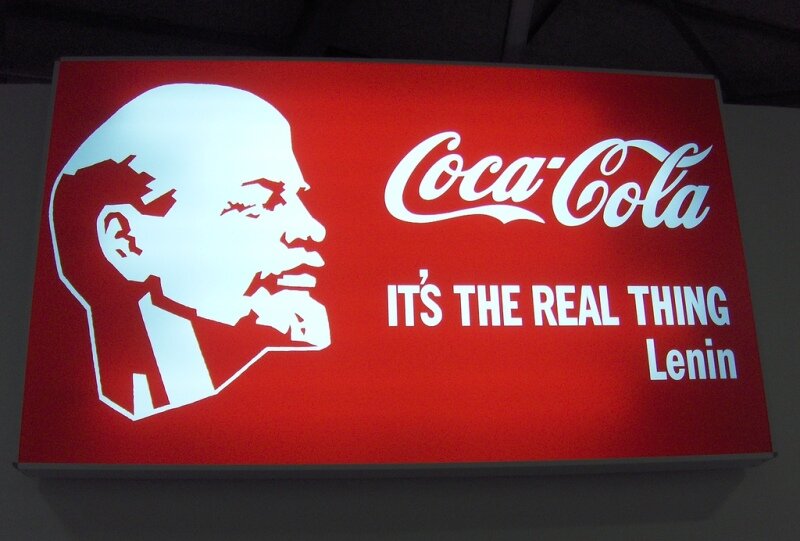

Author: Amy Ross, source: Flickr

In the 1990s, Russia entered the post-imperial phase. It was a period of chaos and social disappointment. Once a mighty nation, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russians suffered from a rapid reduction of international influence. It was something the Kremlin was not prepared for. The fall of communism along with the centrally planned economy hit both the society and the country’s elite badly.

After over 400 years of calling the shots in global politics, Moscow had to revamp itself nearly from scratch. There was no appetite among those in power for a new version of the empire, only nostalgia left after the old one. Historically, the apparent rapprochement with the West came when the Kremlin was as vulnerable as never before.

Andrei Zvyagintsev’s Oscar nominated movie, Leviathan, refers to the Hobbesian vision of the state with a strong sovereign, whose power comes from God. In Russia, messianic visions blend with political pragmatism; the sacred and the profane, the truth and the false reciprocally interpenetrate. It is not easy to lead sitting behind the walls of the Kremlin.

In this context Vladimir Putin was a godsend for Russia. He answered all the country’s needs, if not prayers, by consolidating authority and making Russians proud of their homeland. Putin did not intend to reanimate the empire; he wished to transform it.

The Kremlin’s major fantasy was to be perceived as independent from, and equal to other global players; even though there were no – apart from the nuclear arsenal – solid grounds for it. Moscow has appreciated an exceptional position in its relations with the West. The US and the EU did what they could not to – putting it colloquially – harm Russia’s feelings. Now, as in 2008 in Georgia, Washington and Brussels bear the fruit of its more than a decade-long policy of indolence.

Russia, weak economically and demographically, is a great power in decline, which wishes to be a force to be reckoned with. Yet the West, over the years, has lost the previous capability of being proactive toward Moscow. The intervention in former Yugoslavia, the two rounds of the NATO enlargement, or the abandonment of the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2001 were a show of western strength. However, the quasi-imperial tendencies and the aggressive – but measured – behavior of Vladimir Putin resulted in the special treatment Russia has been receiving to this day; the West got soft. It thought mistakenly that Russia can be reasoned with.

From the tsardom to the Soviet Union to the contemporary Russia, the Russian authorities have intentionally cultivated – for both external as well as internal purposes – the imperial mode of thinking, from which it is fiendishly difficult to break free today. Fortunately for the ruling caste, Russians themselves are not eager to even make an attempt.

Public surveys confirm the image of Russians as the ardent supporters of the iron fist leadership. More than 50 per cent of the society favors the system based on governmental interventionism and two-thirds, in comparison to 14 per cent in 1994, see Moscow as a superpower.

Russians also share a deep negative sentiment toward the West. It has reached its historic apogee with the conflict in Ukraine. The Kremlin, following and fueling the vox populi, portrays itself as non-western. Russians, for their part, are fond of democracy, but they are of the opinion that it should be a tailor-made adaptation accommodating the unique conditions in the country. Russia approaches democracy in its own way, because it believes it is one of a kind.

The Russian restricted system based on the consent of the governed to the manner they are ruled has a characteristic feature. In his novel, On the bottom, the Russian science fiction writer, Dmitry Glukhovsky, depicts Russians as a people blindly believing in the state. Only after drinking alcohol containing nano-robots, which metamorphose the population into rationalists, people start asking questions and thinking independently. This is the gravest danger for the Russian government there is.

Once the society realises that the promised modernisation is nothing but an illusion it might serve as a wake-up call. For that reason, Russians are constantly exposed to political distractions in order to secure their obedience.

For Moscow the future is a pure extension of the past. The vicious Russia-West circle should, at some point, break however. The West needs to stop hoping that Russia might one day be westernised. A friends with benefits relationship between them – at most – is possible. Love is not.

____

This article was first published on New Eastern Europe

Michał Romanowski is a program co-ordinator at the German Marshall Fund of the United States in Warsaw. His foreign and security research interests include Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia. He has written for numerous publications, including The Diplomat, Global Asia, New Eastern Europe, Asia Times and Visegrad Insight. He is a member of the Pacific Forum CSIS Young Leaders Program.